China runs roughshod in South China Sea

May 21, 2020

Hong Kong, May 21 : As dozens of nations have united to request a World Health Organization (WHO) international investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic, something that will stick in the proud gullet of China, Beijing continues to throw its weight around elsewhere. One place seeing more than its fair share of Chinese belligerence is the South China Sea.

The China Coast Guard (CCG), the People's Liberation Army and other government agencies have not slackened their efforts to make the South China Sea their own and to enforce China's version of the law in the disputed maritime area.

This includes, in recent weeks, China dispatching a survey ship into Malaysia's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for seabed investigations, colliding with and sinking a Vietnamese fishing boat, implementing a unilateral fishing moratorium on other nations, shadowing and lambasting US Navy (USN) warships passing through the region, and turning on a weapon control radar against a Philippine warship.

If that were not enough, on 18 April China declared two new municipal districts to control the disputed Paracel and Spratly Islands. A day later, it published the Chinese names of 80 geographic and underwater features in the South China Sea. These are efforts to enforce a fait accompli and assert sovereignty in disregard to others' sensibilities.

The aforementioned Chinese survey ship vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8, accompanied by several CCG and maritime militia vessels, encroached into Malaysia's EEZ on 16 April. This occurred in the vicinity of West Capella, a British drilling ship contracted to Petronas. The action can be seen as a Chinese protest against Malaysia's ongoing energy exploration in disputed waters. In response, the US Navy sailed three different warships nearby.

The region has long been the site of contention, but a picture has emerged of Beijing sensing and exploiting this opportunity to assert itself even more in the South China Sea.

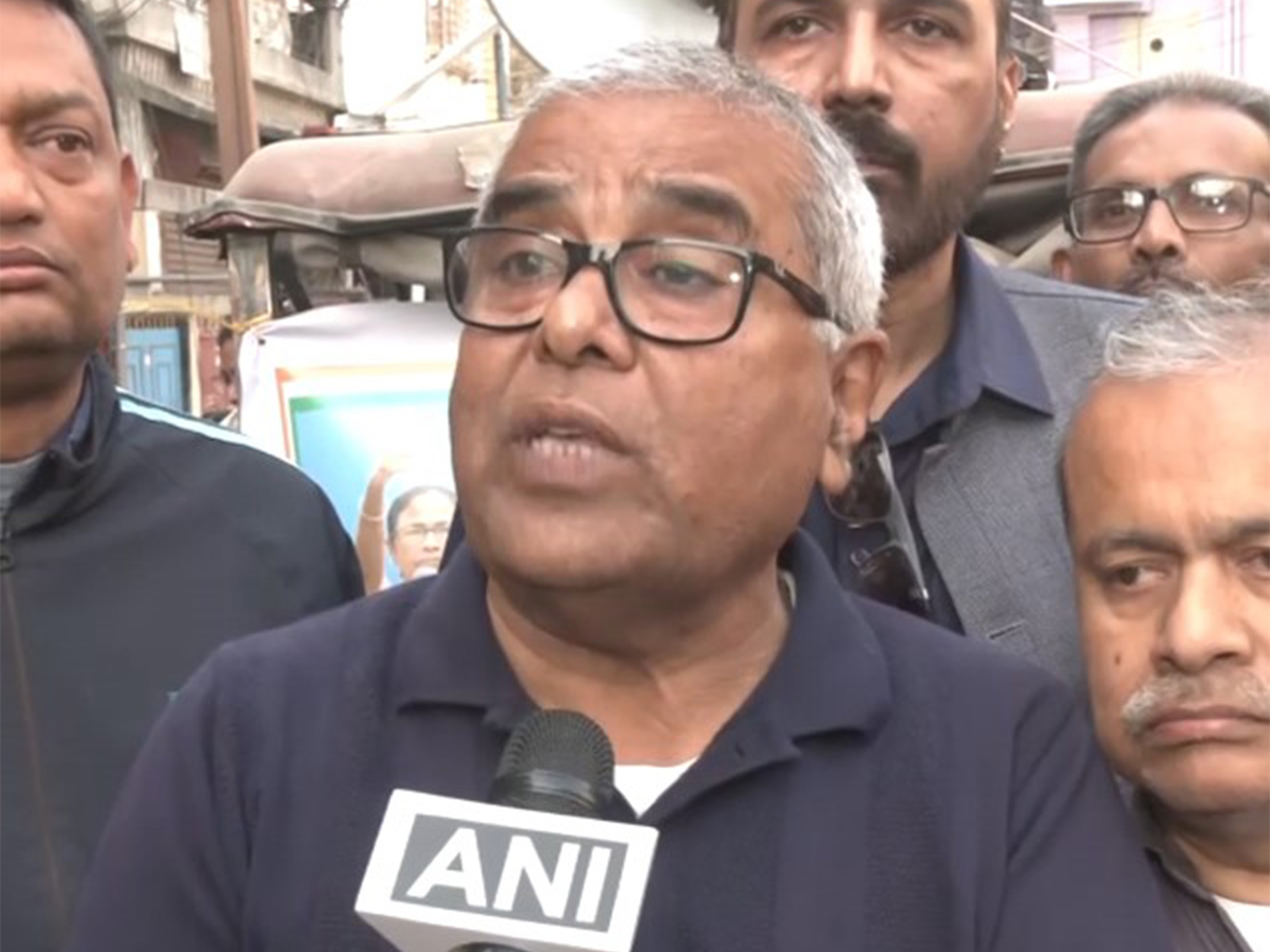

Doctor Tim Huxley, Executive Director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS-Asia), responding to a question from ANI, said, "I think the fact of the matter is that, unfortunately, over the past few weeks, there does seem to have been more activity on the part of China in the South China Sea. China has been pressing on the interests of Southeast Asian countries which have economic activities and occupy features there. This is continuing a trend which began very soon after Xi Jinping became China's leader in late 2012. So what we've seen over the years is escalating and diversifying Chinese pressure and activities."

Huxley continued: "What's often not recognized is that this is not just a question of China being difficult and antisocial in the South China Sea; there almost certainly are very important Chinese strategic objectives behind this pressure on Southeast Asian states' interests. That doesn't justify it, but I mention it to emphasize that this is a long-term trend -it's a reality in the region. And perhaps it would be unrealistic to think that, somehow, because of COVID-19, that the Chinese would slacken off their pressure out of consideration of Southeast Asian countries. No, I think they have major strategic objectives and they will look for opportunities to pursue those."

The Chinese word for "crisis" (weiji) embodies the characters for a situation involving both "danger" and "opportunity". Since the time of Mao Zedong in modern Chinese history, leaders have sought to turn various crises to their advantage. Xi is no different.

The Singapore-based IISS academic, noted, however: "That doesn't mean, just because it's a long-term reality, that Southeast Asian countries and other countries which have important interests in the South China Sea - for example, those countries which value freedom of navigation and free use of airspace - should somehow back off just because China is asserting its interests. There's a long-term competition under way and it has naval, paramilitary, economic, legal and strategic dimensions, and it's important that ASEAN countries work together to protect and promote their interests there."

While this is a fine notion, the reality is quite distant, certainly for now.

Huxley is cognizant of this, admitting that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) "has not been particularly good at managing geopolitical challenges, particularly in the South China Sea. ASEAN has manifested a rather weak position. There's clearly a lack of coordination amongst ASEAN members, and there are differences even between those ASEAN members that have claims, occupy features and have interests in the South China Sea. ASEAN countries, if they want to protect their interests, need to cultivate a mentality that stresses working together, commonality, and hanging together or hanging separately. Because if they don't, that escalated Chinese pressure in the South China Sea is really going to disadvantage them and bring major problems in the future."

Elina Noor, associate professor at the Hawaii-based College of Security Studies, Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, addressing a webinar hosted by the Malaysian-based think-tank Research for Social Advancement (REFSA), offered this observation about Chinese activity as well.

"The specter of Chinese intimidation in the South China Sea is not new. We see incremental intimidation, if not outright harassment, spreading southward in the South China Sea. We've seen Malaysia itself has been under a lot of pressure with increasing incursions by the Chinese."

She also made this important observation, which is particularly cogent as ASEAN attempts to negotiate theSouth China Sea Code of Conduct with China. "What I think is particularly disappointing is that, as this so-called facemask diplomacy is going on, the PRC [People's Republic of China] is seen to be exploiting this pandemic, and continuing to intimidate its neighbours that are trying to respond to this widespread pandemic, illness and death. And I think that really questions the sincerity of China as a partner in trying to resolve this dispute amicably and peacefully."

Thus, what the world is seeing now in the South China Sea is simply a continuation of Chinese policy. As has been seen all around the world, a leopard does not change its spots, even amidst the COVID-19crisis. In many respects, nations' true colours are displayed even more markedly in such a crisis, and that is certainly the case with a China that has been backed into a corner by its own disingenuousness and obfuscation.

Therefore, Huxley sees current South China Sea tensions within a longer-term matrix. According to a presentation he made for REFSA on 12 May: "At the start of 2020, before COVID-19 was a serious challenge, Southeast Asia had already been in a very difficult geopolitical predicament for many years. The signs already were that the plight of the Southeast Asian sub-region was going to become even more difficult to manage over time, and potentially more dangerous as well. In essence, I think there were, indeed there still are, two crucial dimensions to the strategic challenge faced by Southeast Asia."

The IISS executive director also mentioned, "Chinese interference in some Southeast Asian countries has generated widespread wariness in this sub-region over China's policies and tensions. And, unfortunately, China has increasingly come to be seen in parts of Southeast Asia as a rather dangerous revisionist power."

The USA, for a long time acting as a balancing power, is itself contributing to the problem. China has been keen to exploit these fissures too to keep ASEAN under its thumb. "Under the Trump administration, it [the USA] has become less predictable, it's become more transactional, more demanding and, at the same time, for much longer there's been a deeply rooted sense in Southeast Asia and the wider Asia-Pacific that the relative power of the United States has been in decline. Together, all those factors have tended to undermine US influence and have made it seem a less-reliable partner."

Add to this a stress fracture in Southeast Asia over the potential fallout from the USA's increasingly tense competition and potential decoupling with China, for this will affect the sub-region economically and politically.

Huxley named a second relevant factor. "So the second aspect to Southeast Asia's strategic challenge, I think, is from within. It's the evident inevitability of Southeast Asian governments to forge strong common positions on key geopolitical issues. There is a regional security architecture, the ASEAN architecture, that they could - and arguably should - be using for that purpose. This weakness means that Southeast Asia is at really serious risk of being caught up indefinitely on a long-term basis in this major power competition, with individual states coming under ever-increasing stress as they attempt to maintain some sort of semblance of balance in their relations with the major powers. That's only going to become more difficult over time."

ASEAN prides itself on its consensus way of doing business, but that means the ten-nation bloc only ever issues washed-down communiques. Neither does it have the resolve to stand up to China, especially when Chinese lackeys like Cambodia inhibit any progress. Malaysia and the current Philippine administration have been relatively acquiescent to China's demanding behaviour, so it will be interesting to see whether COVID-19 changes their stance in any way.

Prasanth Parameswaran, writing for The Jamestown Foundation about Malaysia's relations with China, explained: "Malaysia has traditionally pursued what might be termed a 'playing it safe' approach with respect to the South China Sea, where it pursues a combination of diplomatic, economic, legal and security initiatives to secure its interests as a claimant state, while also being careful not to disrupt its bilateral relationship with the PRC." After all, China is the country's largest trading partner.

Parameswaran acknowledged, though: "Over the past few years, Malaysian policymakers have recalibrated aspects of the country's South China Sea strategy as they become more aware of the challenges posed by China's assertiveness." For example, Kuala Lumpur launched a diplomatic protest against Chinese incursions, has stepped up patrols in places like Luconia Shoals, filed a joint submission claim with Vietnam, and submitted a new extended continental shelf claim to the United Nations last December.

However, it will not be easy. Malaysia's defence capabilities vis-a-vis China were already constrained even before the strictures of COVID-19. Parameswaran noted, "While Malaysia's shortfall in maritime capabilities has long been recognized, China's assertiveness in the South China Sea has exposed these limitations in recent months and the Southeast Asian state has faced issues in ramping up its defense budget."

So, how has COVID-19 impacted the South China Sea and Chinese activities there?

Huxley offered this summary. "The answer is, I think, COVID-19 has accentuated the regional predicament, but at the same time hasn't fundamentally changed it. Any idea that the pandemic might provide some sort of respite from strategic competition has been misplaced. China has not slackened its pressure on Southeast Asia. Indeed, the signs are that it has attempted to take advantage of Southeast Asian states' preoccupation with countering the pandemic, and also has taken advantage of the compromising effect of COVID-19 on naval readiness of the United States in the region. And as a result, China has heightened its pressure in the South China Sea."