Nepal: Citizenship ordinance - a victory for Madhes

May 24, 2021

Kathmandu [Nepal], May 25 : The latest ordinance to amend the Nepali Citizenship Act, introduced by the President of Nepal Bidya Bhandari, indeed marks a historical phase in Nepali politics and induces a sense of achievement among the madhesis.

The essence and relevance of the ordinance has however been lost in the intricate web of political cross currents the country has witnessed in the last few days. The ordinance marks the end of a long struggle by the madhesis on at least one of the several core issues regarding the grant of citizenship to large number of madhesis who are born in Nepal and have a right to citizenship.

The present ordinance is likely to favourably benefit more than 5 lakh people who have been waiting on the sidelines for such a law. There would be a peter down effect on successive generations as well. With the citizenship ordinance being issued, within the madhesi community, there is a feeling of relief with some hope of the possibility of redressal of some of their other demands as well, even though the latest outcome was a result of a political tussle at the centre.

Generations of madhesis have struggled over the years drawing the attention of successive rulers - from the monarchs to the political leaders, who promised delivery on the citizenship issue, but to no avail. Leaders in Kathmandu have played with the sentiments of the Madhesis exploiting their desperation to have their demands addressed while at the same time hyping nationalist sentiments in a manner so as to shrink the space for the madhesis to achieve their objectives.

In the eyes of the Kathmandu elite, the madhesis have been traditionally viewed with suspicion and considered as an extension of India. Moreover, with the narrative of "Anti Indianism being Nepali nationalism" forming the backbone of nationalist sentiments from times immemorial, the madhesi demands remained unaddressed as successive generations of politicians exploited the madhesis to bind the country together on a nationalist agenda.

The reign of King Mahendra Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev from 1955 to 1972, for instance, witnessed a form of Nepali nationalism that hinged on building a strong hill (pahadi) mentality bringing to together pahadi culture, traditions and values at the cost of the other ethnic groups and minorities.

This was aimed at segregating the madhesis and the other minorities from the rest of the population. Land owning laws were implemented during this phase which clearly discriminated against the madhesis as hordes of hill people, including those from North Bengal, were brought into the Terai region for settling down, thus cutting into the madhesi population. Hope for some respite among the madhesis in the form of an inclusive constitution that would address their problems also lost steam with successive constitutions failing to address their issues in spite of promises made to the contrary.

There is a belief among the madhesis that in spite of bitter differences between the communists and the democrats (Nepali Congress), when it comes to the madhesi demands, all political parties hold a unanimous view or rather the pahadis come together. It is for this reason that in spite of different parties coming to power from time to time, none of them have been able to deliver on the madhesi issues.

Frustrated at the lack of support from various governments, the madhesis have also held protests over the years to draw the attention of the government in Kathmandu but without any success. The first sign of political activism by the madhesis came to notice in 1959 when a party called the Terai Congress contested the country's first national elections but lost miserably.

Thereafter, in the 1990s, a former Nepali Congress leader named Gajendra Narayan Singh formed the Sadbhavana Party to advocate for Madhesi rights. But it was not until 2007 that the Madhes movement really gained force with months of street protests held in 2007 and 2008, against the political indifference to their plight. The 2015 hold up of supplies from India for several months, which eventually created deep-rooted anti-India sentiments in Nepal, was also a result of a constitution that failed to address the Madhesi demands.

Meanwhile, to ward off negative sentiments, the madhesi leaders have done their bit in being recognized and seen as Nepali first and madhesis later when it comes to critical national security issues. For instance, in June 2020 all madhesi leaders eagerly participated in the constitutional amendment voting introducing the new map of Nepal.

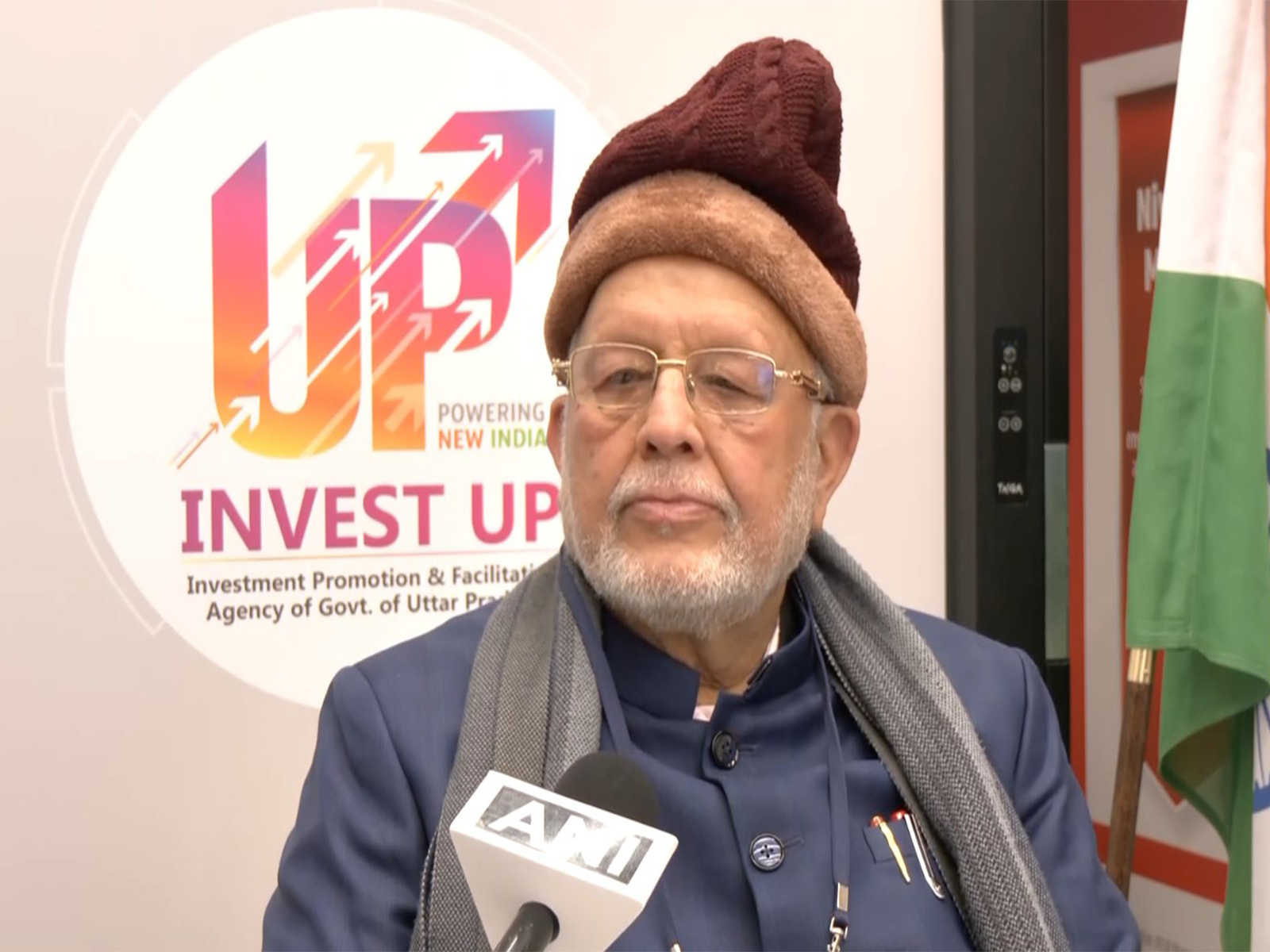

The entire madhesi leadership unanimously supported the new map, siding with the nation sending out a clear signal that for them the nation came first. JSPN leader Rajendra Mahato in fact made a fiery speech drawing the attention of all Nepalis to the decision by madhesi leaders to support the map issue, inspite of the fact that the madhesi demands remained unaddressed.

Among the political parties, it was the RJP - an amalgamation of six madhesi parties which has lately come forward pushing the madhesi demands, besides the Samajwadi party. Unfortunately, the caste-based politics that dominates the madhes has made it difficult for madhesi political parties to remain consolidated on madhesi issues.

In this backdrop, the determination with which leader of the JSPN, Mahant Thakur has been pursuing the objective of getting through the citizenship issue and setting up of a task force for undertaking constitutional amendment, is a clear indication of his eagerness to address these issues while he continues to dominate the madhesi political space. For Mahant Thakur personally, it has been a long journey from the days when the madhesis were looked down with utter disgust and hatred by the pahadis to a stage in 2018 when being the senior-most parliamentarian, he was accorded the honour of opening the first session of the Parliament under the Oli government.

He has seen the days when madhesis travelling to Kathmandu were required to carry a long folded document of identity which was more like a passport, without which they were not allowed entry into the capital. Those were times when the madhesis were looked down upon with locals in Kathmandu referring to them as "dhotiwalas" or using other derogatory terminologies. Stories abound of how application for jobs by qualified madhesis were rejected outrightly and how special favours were shown to pahadis as against madhesis in selection processes.

It is thus indeed a sense of deja vu that has overwhelmed Mahant Thakur, Rajendra Mahato and the others with the citizenship ordinance coming into force as this amounts to history being made. They are not concerned about who delivers justice as long as it serves the purpose of the madhesis.

The celebrations that marked the citizenship ordinance in the madhes goes to show the tremendous positive narrative it has created in the Terai region. The gesture is also indicative of the will and desire of the government to address other similar issues associated with various marginalized communities such as the Janjatis, Tharus, Gurungs, Limbus etc. With the task force likely to be set up for constitutional amendment by the Oli government, a second step would be achieved in the madhesis' endeavour to strive for their demands.

While all the leaders who have today come together to oppose PM Oli feel that the latter has delivered on the citizenship issue as part of a political compromise, the fact remains that all of them had the opportunity to address the madhesi issues, including the citizenship issue, at some point or the other, but refrained from doing so for fear of being branded anti-national.

In that sense, political analysts feel that credit should be given to PM Oli for mustering the courage to overlook all concerns to deliver on the citizenship issue. It is he who can possibly deliver on the other madhesi demands as well after calibrating domestic sentiments. The support extended by Mahant Thakur and Rajendra Mahato to PM Oli has undoubtedly produced positive dividends for both sides.